- BRNN

- BRI News

- BRNN News

- Database

Official Documents Polices and Regulations

Inter-government Documents International Cooperation BRI Countries

Business Guide Economic Data BRI Data

Trade

Investment Projects Latest projects

Cases - Content Pool

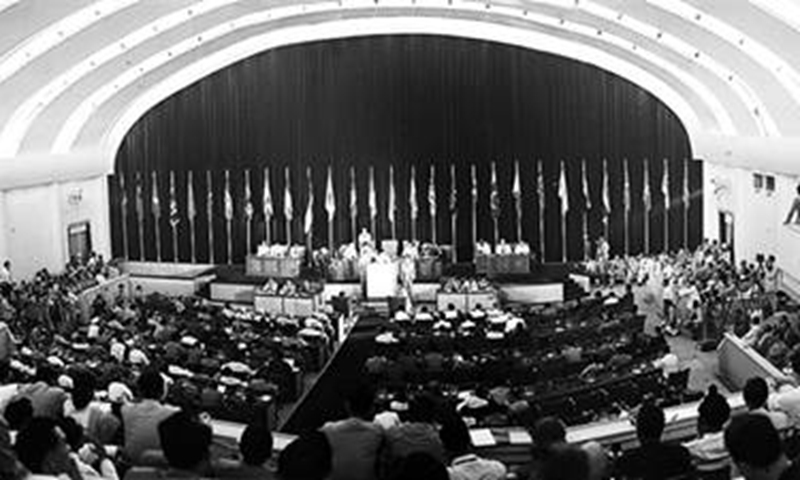

On 18 April 1955, the Asian-African Conference was convened in Bandung, a picturesque mountainous city in Indonesia. As the first large-scale international conference initiated and participated exclusively by Asian and African countries, the meeting riveted great international attention as it echoed the upsurge of national liberation movements across the world at that time. Against all odds, Premier Zhou Enlai, who was concurrrently China’s Foreign Minister, led the Chinese delegation to the Conference and put forward the resounding principle of “seeking common ground while shelving differences.” His proposal not only contributed to the successful conclusion of the Conference, but also greatly enriched the body of international relations. Premier Zhou’s attendance at the Bandung Conference is still much talked about till this day.

Looking back on that part of history, one could see that the Chinese delegation’s participation at Bandung had a bumpy start. Hostile forces at home and abroad did not want to see Chinese Communists making their voice heard on the world stage or New China raising its international profile. The secret service from Taiwan engineered the world-astonishing Kashmir Princess plane crash, an assassination attempt targeted at Zhou Enlai. Fortunately, Zhou himself was not on board for an unplanned visit to Myanmar. But in the wake of the incident, whether the Chinese delegation would still make it to the Conference, and whether the Conference would be held as planned became a question on many people’s mind. Despite serious security risks, Zhou decided to go to Bandung nevertheless, a display of China’s resolve to promote international peace in defiance of all difficulties.

Neither did the final success of the Conference come easily. The 29 participating countries, though many warmly supporting the Conference and hoping for its full success, had divergent views on major international issues due to different national realities. Compounding the situation, the US-led West were trying every means to lure Asian and African countries to their side to form a military bloc against socialist countries. Therefore, while most participating countries called for peace, a few lashed out at communism and questioned China’s choice of the socialist road. The amicable climate of the Conference was overshadowed.

At the critical moment, Premier Zhou made a strategic decision: instead of being among the first to speak, he decided to wait till others finish to make a targeted response. He did not read out his prepared speech: instead, he had his printed speech circulated among the delegates, and spoke off-hand. In his impromptu statement, he rose above a tit-for-tat response to the unfriendly even hostile statements made against China, to stress that the Chinese delegation had come to seek unity, not to pick a fight; to find common ground, not to create differences. He underlined China’s readiness to establish normal relations with Asian and African countries, and for that matter with all countries in the world, but first of all with its neighbors, on the basis of the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence. He also articulated the position of the Chinese Communists: while we are never shy of expressing our faith in communism or in the strength of the socialist system, the Bandung Conference is not supposed to be the venue to market anyone’s ideology or any country’s political system.

His words immediately won support from most participating countries, thus easing the tense atmosphere and striking a positive tone for the Conference. On the sidelines of the plenary sessions, the Chinese delegation actively reached out to other delegations, contributing its share to the adoption of the Final Communiqué of the Asian-African Conference. Drawing on China’s input, the Communiqué put forth 10 principles for living together in peace with one another and developing friendly cooperation, which embodied a new type of international relations featuring solidarity, friendship and cooperation. The main part of the 10 principles has much in common with the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence.

The Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence were first expounded by Zhou Enlai when he met a visiting Indian delegation at the end of 1953. At first, the principles were designed to address issues between China and India, especially for India’s relations with China’s Tibet region. In April 1954, the Agreement Between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of India on Trade and Intercourse Between Tibet Region of China and India was signed; at the beginning of the Agreement, the Five Principles were defined as the guidelines for China-India relations. During his visit to India and Myanmar in June later that year, Premier Zhou elaborated on the underlying ideas of the Five Principles with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru of India and Prime Minister U Nu of Myanmar. Both leaders agreed with the principles; hence they were written into the joint statements China issued respectively with India and Myanmar. It became a powerful weapon of New China to break the US-led Western blockade and expand foreign exchanges.

More than six decades of diplomatic experience shows that the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence are not only the cornerstone of China’s foreign policy but are also widely recognized by the international community. Throughout the years, China has been committed to forging ahead with other countries by seeking common ground while shelving differences. It is a path that accords with both the trend of history and the progress of humanity. More and more countries will join China on this right path.

Zhou Enlai at the Bandung Conference

Zhou making his statement at the Bandung Conferenc

Inside the Bandung Conference hall

People swarming around Zhou for autographs

Tel:86-10-65368972, 86-10-65369967