- BRNN

- BRI News

- BRNN News

- Database

Official Documents Polices and Regulations

Inter-government Documents International Cooperation BRI Countries

Business Guide Economic Data BRI Data

Trade

Investment Projects Latest projects

Cases - Content Pool

An aerial view of the former site of the Mukden Allied POW Camp in Dadong district, Shenyang, northeast China's Liaoning Province. (People's Daily Online/Qiu Yuzhe)

In October 1992, a former prisoner of war wrote to the U.S. Consulate General in Shenyang, located in northeast China's Liaoning Province. His letter recounted the suffering he experienced at the Mukden Allied POW Camp during World War II and conveyed his desire to revisit the site.

But where exactly was the Mukden Allied POW Camp located? At the time, no one knew. After Japan's unconditional surrender in World War II, nearly all records and documents about the camp were destroyed, and its exact location remained a mystery for many years.

After receiving the letter, Yang Jing, then a consular assistant at the U.S. Consulate General in Shenyang, began a painstaking search. A year later, Yang finally identified the former site of the camp in Shenyang's Dadong district.

In 2007, restoration work began at the site. In 2013, it was officially opened to the public.

A restored watchtower and the remains of barracks at the former site of the Mukden Allied POW Camp in Dadong district, Shenyang, northeast China's Liaoning Province. (People's Daily Online/Qiu Yuzhe)

After the September 18 Incident in 1931, northeast China became a production base for Japan's war of aggression. As Japan expanded its wars and battlefronts, labor shortages became acute. The Japanese military exploited both POWs — mainly from the U.K. and U.S. — and Chinese civilians and captured soldiers, forcing them into harsh labor units.

Japan established 18 POW camps during World War II, eight within Japan itself and 10 in occupied territories. The Shenyang facility stands as the most intact overseas POW camp still in existence.

In 1942, the Japanese transferred POWs with technical skills in machining and manufacturing, captured in the Pacific Theater, to Shenyang. They were imprisoned in the camp and sent to Japanese-run factories as forced labor to address the manpower and resource shortages caused by Japan's constant troop deployments and expanding war of aggression.

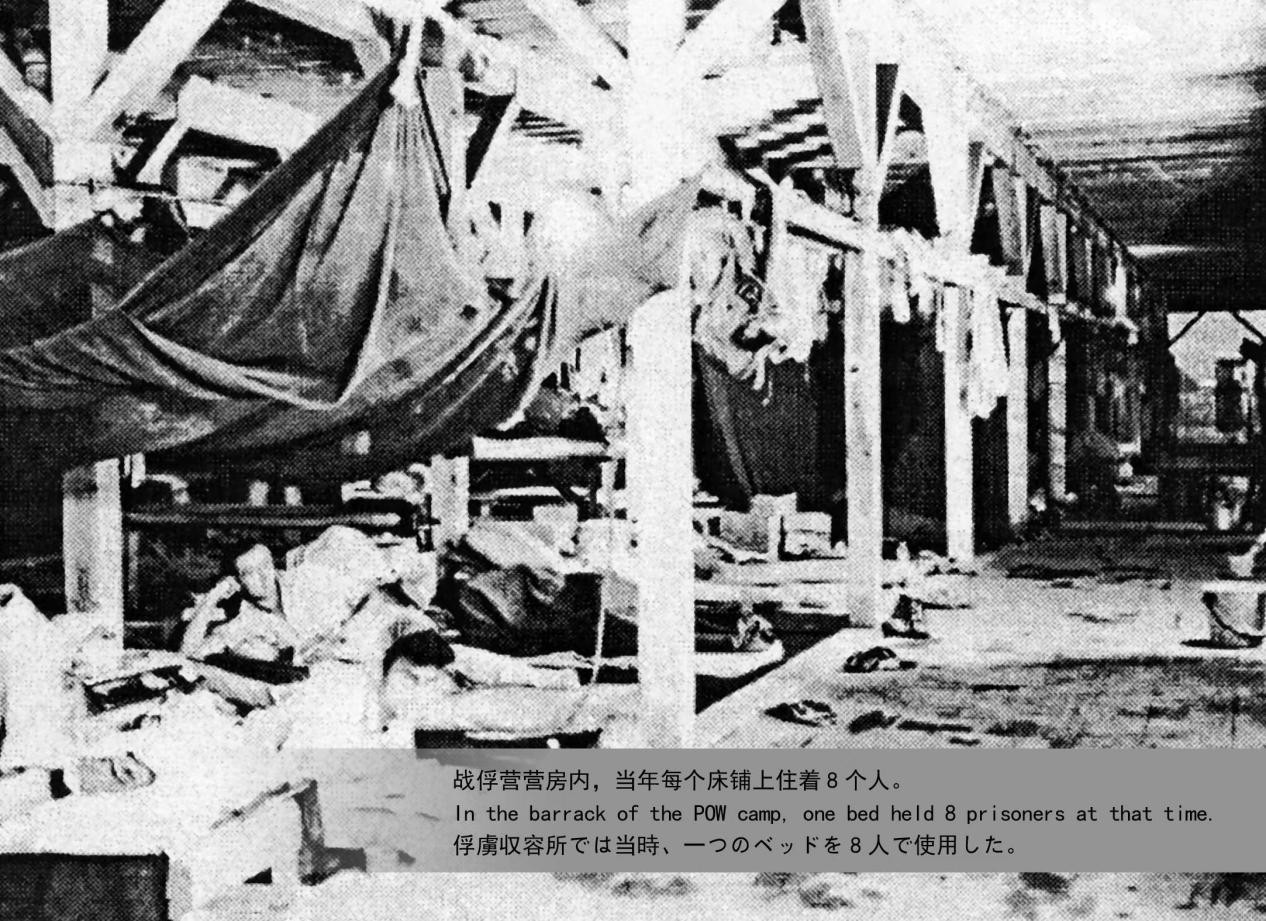

A barrack at the former site of the Mukden Allied POW Camp in Dadong district, Shenyang, northeast China's Liaoning Province. (Photo courtesy of the 9.18 Historical Museum in Shenyang)

Between November 1942 and August 1945, the camp held more than 2,000 POWs from the Pacific Theater, including Americans, British, Australians, Dutch, Canadians, New Zealanders and Singaporeans..

A group photo showing rescued POWs from August 1945. (Photo courtesy of the 9.18 Historical Museum in Shenyang)

British Major Robert Peaty was among the first POWs held at the camp. After the war, he compiled and expanded his diary, describing in detail the punishments inflicted by Japanese guards.

"A bowl of water was placed on our outstretched arms. If a drop spilled, we were beaten with a rattan cane or a sword scabbard. Sometimes we were forced to kneel with our hands on our heads. If we shifted, our legs were struck mercilessly," he recalled.

Reconstructed bunks inside the barracks at the former site of the Mukden Allied POW Camp in Dadong district, Shenyang, northeast China's Liaoning Province. (People's Daily Online/Qiu Yuzhe)

In 2007, former POW Robert Brown revisited the site. He called the experience "absolutely dreadful."

"Food was scarce, medicine almost nonexistent, and the cold unbearable. One by one, people died. In temperatures of minus 30 to 40 degrees Celsius, the ground was too frozen to dig graves, so bodies were kept in a hut until spring," he said.

The combination of prolonged abuse and harsh conditions resulted in a 16 percent death rate at the camp, significantly higher than most other POW facilities.

The prisoners also carried a heavy sense of guilt. Forced to produce goods for Japan's war machine, they feared their labor would be used against their own countries. Even under strict surveillance, they found ways to resist by sabotaging products or setting fires in the factories.

Over nearly three years of captivity, the prisoners endured hunger, disease, and cruelty. In that dark time, their only comfort came from Chinese workers and villagers who, despite their own hardships, offered help.

Three American POWs successfully escaped on June 21, 1943, with crucial assistance from Chinese worker Gao Dechun.

Gao had once noticed American POW Joe Bill Chastain slip a map from a Japanese officer's drawer. Realizing he was planning an escape, Gao quietly bought another map at the market with his own money and placed it back in the drawer to avoid arousing suspicion.

After 11 days on the run, however, Chastain and the others were captured. On July 31, they were executed. Because Gao had worked alongside Chastain, the Japanese suspected his involvement. He was arrested, tortured, and eventually sentenced to 10 years in prison for anti-Manchukuo and anti-Japanese activities.

Gao remained imprisoned until Japan's surrender in 1945, when he finally regained his freedom.

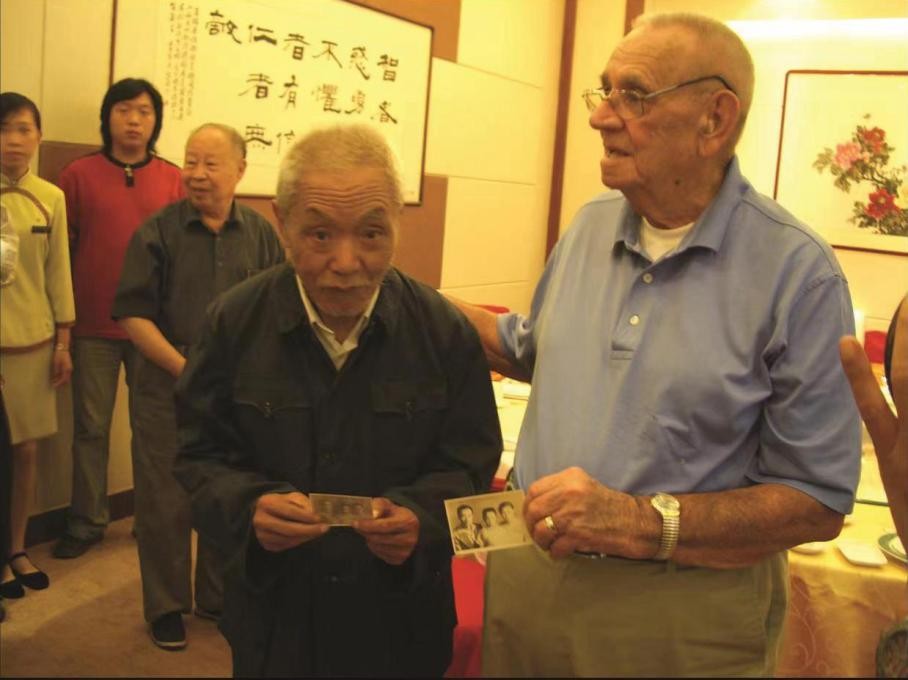

Former POW Harold Bell Carter [u1] returns to Shenyang in September 2005, carrying a photo as he searches for his Chinese friend. He eventually found his friend's descendants. (Photo courtesy of the 9.18 Historical Museum in Shenyang)

The number "266" was assigned to American POW Neil Gagliano. About 10 meters away worked an apprentice named Li Lishui, who remembered only his number, not his name. Each time Gagliano caught sight of him, he would smile, a gesture that left a lasting impression on the young apprentice.

One day, some cucumbers fell off a passing vegetable cart. Li found that prisoner 266 was watching him. He picked up two cucumbers and threw them to Gagliano, who responded with an enthusiastic "OK" gesture. For a starving prisoner, those cucumbers were an unforgettable act of kindness.

Li had almost forgotten about the two cucumbers until U.S. journalists interviewed him in 2002. Later, Gagliano sent him a photo of himself and a letter, telling him that he was prisoner 266.

Ge Qingyu, a staff member at a Japanese factory, taught POWs Chinese and even helped American POW Roland Kenneth Towery smuggle out factory tires and axle bearings in exchange for food.

Following his release, Towery visited Ge's home, met his wife and young son, and exchanged keepsakes. After returning to the U.S., Towery worked as a journalist, held senior roles in U.S. media, and was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1955.

In 2005, which marked the 60th anniversary of the victory of the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War, the U.S. government awarded commendations to Li Lishui, Gao Dechun and Ge Qingyu, recognizing their courage and humanity in aiding American POWs under life-threatening circumstances.

Tel:86-10-65363107, 86-10-65368220, 86-10-65363106